The first comprehensive assessment of where the Earth’s excess heat is accumulating has been released by GCOS. Reporting in the journal Earth System Science Data, the group of more than 30 researchers from scientific institutions around the world tracked and quantified global heat storage from 1960 to 2018 to answer the question “where does the heat go”

Heat stored in the Earth system

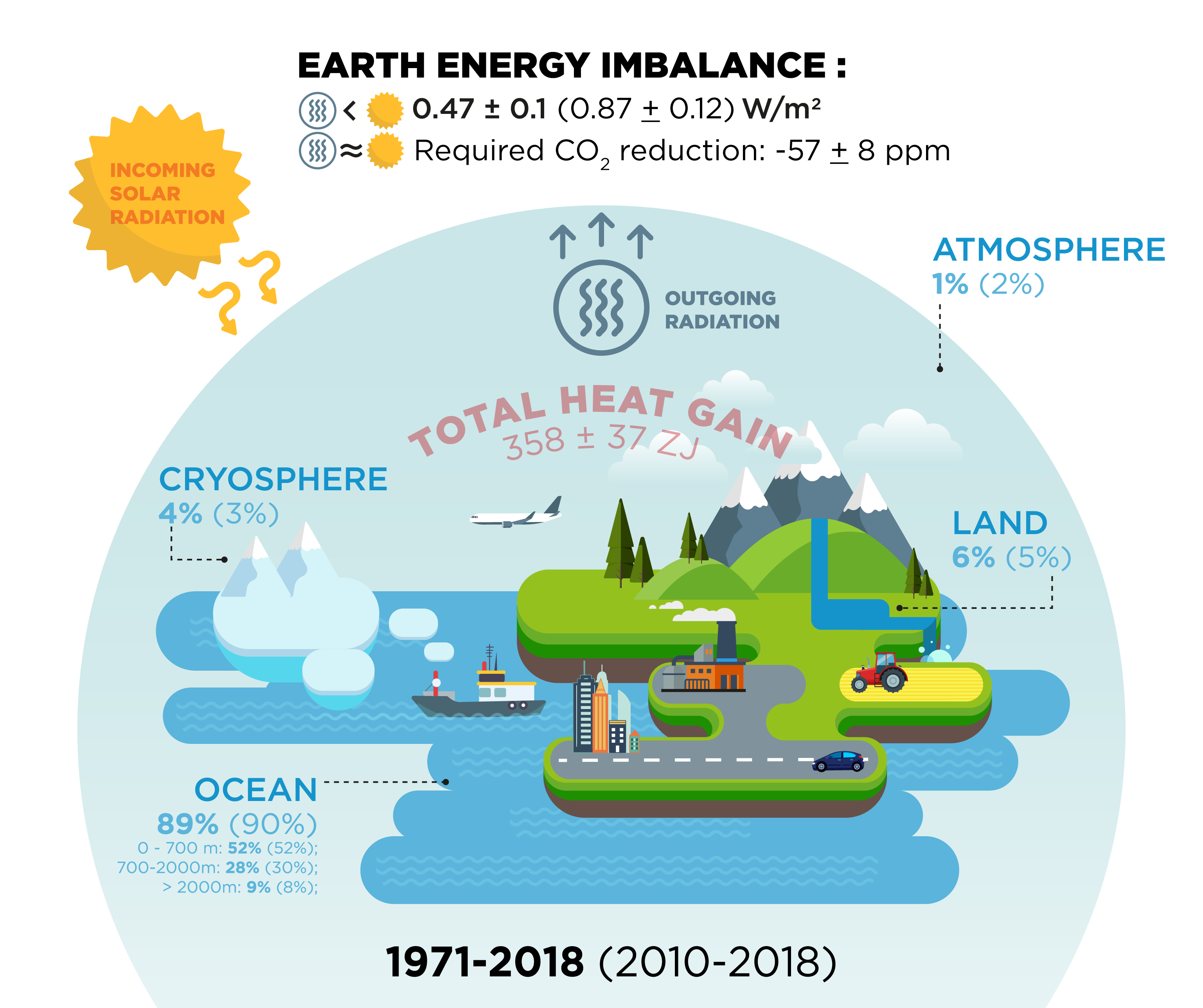

The Earth Energy Imbalance (EEI), the difference between the amount of energy from the sun arriving at the Earth and the amount returning to space, serves as a fundamental metric to allow the scientific community and the public to assess how well the world responds to the task of bringing climate change under control.

The new study represents the most accurate, state-of-the-art heat inventory study to date. It indicates that the Earth Energy Imbalance continues to grow unabated and has doubled in the past decade (2010-2018) compared against the 1971-2018 mean value.

Only approximately 1% of this heat resides in the atmosphere. The vast majority of excess heat (89%) is absorbed by the ocean. New assessments of borehole measurements show that the land heating is 6%. About 4% of excess heat causes loss (melting) of both land ice and floating ice.

Direct impacts of this heating, driven by heat-trapping anthropogenic carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, include sea-level rise, ice loss, and warming of the ocean, land and atmosphere. The results also show that EEI not only continues, it increases: the EEI amounted to 0.87 + 0.12 W/m2 during 2010-2018.

Stabilization of climate change requires the EEI to be reduced to approximately zero to regain a quasi-equilibrium state in the Earth system.

This study calculates that the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere must be reduced from the present concentration of nearly 410 ppm to approximately 350 ppm to bring the Earth back towards energy balance.

“The EEI calculation is hence the best single metric we have of how well we are doing in our attempts to bring climate change under control. Improved quantification and reduced uncertainties of the EEI can only be achieved through sustained international multi-disciplinary collaboration and enhanced global climate observations with extensions to cover important gaps such as the deep ocean and the cryosphere,” said the study, led by Karina von Schuckmann of Mercator Ocean International.

The publication is available here

Last Update : Sep 2020